what’s cookin’

How are you doing, gang? Are we really only into the third week of the year? So much horrific shit has happened, the mind reels. The LA wildfires, the orange terror was inaugurated, and now San Francisco has lost one of its crown jewels, chef Charles Phan. It’s all so deeply exhausting. Sending the biggest hugs to everyone right now.

I’m glad I spent most of Monday’s holiday cooking and staying away from social media, because processing Tuesday’s official news of the passing of chef Charles Phan has been a lot. I have spent the past two days speaking with chefs and friends and colleagues about him, listening to their stories and feeling their grief, while writing this tribute to him in today’s column. We all send tremendous condolences to Phan’s loving family and many friends and colleagues.

I hoped I was going to be able to send this out yesterday, but I needed more time to write this the way I needed to, so that’s why you’re receiving the hopper today. (It has been braising and couldn’t be rushed.) I could easily spend a week on this piece, to be honest—Charles’s vast community has much to say and share about him, and he means so much to our city. Since I’ve been up writing this tribute until 3am the past two nights, I didn’t have any more time or bandwidth to write the news as well—you’ll get it next week. This one-woman show has hit 5,000 words, so I need to stop typing right now.

I’m sending today’s newsletter to all subscribers (paid and free) at once, but I want to give a special and heartfelt thanks to all of you who are supporting subscribers—your generous financial support makes it possible for me to write longer pieces like today’s tribute. We’re now in the renewal period for many of you early subscribers (mwah), and I really hope you’ll stick with me—I need your support now more than ever, especially since I no longer have my rent-controlled apartment and am trying to manage paying triple my former rent right now, and it hasn’t been easy (real talk, people).

Our city also needs your support—tablehopper is all about building community and shining a light on the people who make our culinary and local culture interesting and vibrant and unique (and delicious). “Tightening your belt” and canceling your subscription constricts my ability to take the time to feature all these places and people and events—I have a lot of heart and passion, but I don’t have a millionaire backer or financial institution covering the costs to write and produce this weekly publication and keep me afloat. I depend upon you, dear readers.

Maybe you had a good year (yes!), and you’d like to upgrade your subscription to the regular rate of $149, or perhaps you’re feeling like a Patron and would like to help someone else enjoy a subsidized subscription (while enjoying some extra benefits). You can sign into your account at tablehopper.com and easily upgrade your subscription level—just click the little blue person or plus sign in the bottom right corner. Feel like surprising someone with a gift subscription? Right this way...

When I don’t have enough income from subscriptions, then I have to take on other work, which diminishes my ability to focus completely on tablehopper. I know it sucks to have to pay for so many subscriptions in order to read anything online right now—trust me, I get it—but it’s the only way for most journalists to survive, like this lady in this expensive city. If you want my well-seasoned perspective on our culinary world to be able to continue (tablehopper is turning 19 in February!), especially during these dark and difficult times, then starting (or renewing or upgrading) your subscription to tablehopper is literally putting gas in my tank so we can move forward, together.

If you’re a free subscriber, you should know you’re missing out on a big feature I sent to supporting subscribers this past weekend: The Hopper Notebook: Seven of My Top Traditional and Iconic Pasta Dishes in San Francisco. I’m sharing some real gems and deep cuts, and they’re not what you’ll see on every other “Best Pasta in San Francisco” list (this is what happens when you’re half-Italian, and you’ve been living in San Francisco for 30 years, and writing about our food scene for over 20 of those years). Become a supporting subscriber and enjoy my pasta parade, because I know we could all use some comfort food right about now.

Before I sign off, big congrats to all the James Beard Award semifinalists—you can read the full list of 2025 Restaurant and Chef Award semifinalists on the James Beard Foundation website. I especially loved seeing Stuart Brioza and Nicole Krasinski (The Anchovy Bar, State Bird Provisions, and The Progress) be nominated for Outstanding Restaurateur, and Suzette Gresham (Acquerello) for Outstanding Chef, plus The Halfway Club for the new category of Best New Bar. Awwww. There are a bunch more local folks on the list, best of luck to all! The Restaurant and Chef Award nominees will be announced on Wednesday April 2nd, and winners will be celebrated at the James Beard Restaurant and Chef Awards ceremony on Monday June 16th, at the Lyric Opera of Chicago.

OK, let’s dive in. Take good care of yourself, and others.

Love always,

~Marcia

the chatterbox

San Francisco Mourns the Unexpected Passing of Chef Charles Phan, the Heart of Our Culinary Community and an Absolute Legend

A pilot light for one of the hottest burners of San Francisco’s culinary stove has sadly gone out. The brutal news that visionary chef, restaurateur, and cookbook author Charles Phan of the Slanted Door Group has unexpectedly died at the age of 62 is a tremendous shock, and has created a massive wave of grief and remembrance among his vast community.

I received word that he had a heart attack last week (which is extra-poignant when you consider what a big heart he had), and waited to mention the news until the family was ready to share an official announcement, which they posted on Instagram on Tuesday. It has been so moving to see the many stories, pictures, homages, and tributes roll out from his expansive and loving community as the ripples of the heartbreaking news started to spread. Damn, why did we just lose one of the really good ones? It’s just awful.

Charles was a supernova of talent, an inspiration, and a huge part of San Francisco’s culinary pride. Our gem. But what I’m seeing the most in these tributes is how magnanimously Charles looked after his fellow chefs and their restaurant projects, from giving advice to providing resources. I have heard repeatedly how he’d check in on folks if they were opening a restaurant, text, swing by, meet up for a late-night bite (and get some classic “cold tea” at Yuet Lee back in the day), make referrals, intros, and offer his space, anything they needed—even buying them a smoker.

Laurence Jossel of Nopa fittingly called him “Uncle Charles,” and noted that everyone in the chef community is “upside-down” about his death, but has been so touched hearing everyone else’s stories about how generous he was. Jossel shares: “He would always ask ‘How can I help? What do you need?’ He just made it happen. If he saw that you were burnt out or tired, he’d say, ‘Here are my keys. Go chill in my place in Napa.’ He’d give give give. When we were opening Nopa, he said we could take what we needed from his storage under Slanted Door on Valencia. We needed barstools, so we took the rectangular barstools and routed them into square seats. So, yes, the seats at Nopa’s community table are the original Slanted Door barstools, and they are still with us.”

I caught up with Gayle Pirie of Foreign Cinema, who has had Charles as a diehard regular for all of the restaurant’s 25 years. She says when they launched brunch, Charles would bring his entire family every Sunday—he would host a table of eight to ten guests. She counts his support as integral to the success of Foreign Cinema’s brunch, which grew to be one of San Francisco’s best. She said, “He was part of the foundation of the success of Foreign Cinema. He was always encouraging us. A week before we opened the restaurant, he was counseling us. And after we opened, he was always bringing in neat friends. He’d be at the bar at least twice a month, manning the well, eating through the menu at 9:30pm, the oysters, the ceviche, the tartare, the crab. He was complimentary. A chef loves it when a chef is eating at their restaurant!”

Charles was a giant, a lion, a pillar of our culinary world who cut a wide swath for everyone who was to come after—and even with all his renown and awards and accolades, he remained ever-humble. When you think about all the swagger most chefs put on with just a pinch of his bona fides—let alone having the top-grossing, independently owned restaurant in California 20 years after opening—but Charles always kept it real like a true G.

Longtime customer and close friend Bob Rosner shared: “He was so humble—he wasn’t like a king, but he was a king. And, for SF, he was always our Charles. Oh, and all the famous guests that came. They were both in awe and treated them like everyone else. Yoko Ono was there eating lunch near me.” I remember when President Bill Clinton dined at Slanted Door in 2000—be sure to watch this lovely retrospective video from KQED with Charles telling the story of Clinton’s visit, as well as his family’s harrowing story of fleeing Da Lat, South Vietnam, on a cargo ship just before the fall of Saigon in 1975, and eventually immigrating to the United States.

His former publicist and marketing wizard, Faith Wheeler, who was with Charles for 17 years (from the very first days of the Slanted Door), shared this story with me that she included in a farewell letter she has been writing to him the past few days: “I’ll never forget your speech at your father’s funeral, you explained how somewhere in the middle of the sea, in 1975 when the family had left during the fall of Saigon, your Mom said: ‘Charles, it’s up to you now. We are left with nothing.’ And you watched your Dad trade his business suit for a broom. All of it, from the boat to Guam to the internment camp in Arizona, to your tiny apartment in Chinatown with your six siblings, to dropping out of U.C. Berkeley to help out your family at the sewing shop. It all made you remarkable.”

He was also deeply, magnificently generous. It’s unreal to imagine all the fundraisers and charity events he cooked for, all the auctions he was asked to contribute to, the cooking demos, the appearances, the catering, the weddings, the private dinners… It’s hard enough to run your business, let alone one with multiple locations, but to also attend hundreds of events and make appearances is another thing entirely. He showed up hard and always gave back.

With his growing restaurant group, he practically employed his entire family, providing jobs for siblings and aunties and uncles and cousins and spouses and more—he created a kind of employment agency that included 17 members of his family. I can only imagine the internal concerns about how to move forward right now, but their PR said in an email to media: “While this was sudden and shocking to many of us, we will endure as the Slanted Door has for almost 30 years. The restaurants will continue to operate under the leadership of our management team as we navigate this transition.” Big hugs and sending deep condolences to Michelle Mah, the group’s director of culinary operations, who has been working with Charles since 2011—they were best friends.

It’s so sad to think he was on the brink of reopening the Slanted Door in the restaurant’s original location on Valencia Street, 30 years later. (I would like to believe the family is still going to do it.) I moved to San Francisco in 1994, and Charles opened up the Slanted Door on Valencia in 1995. That restaurant was so hot—it was a huge draw to the neighborhood (which paved the way for other restaurants to open there), with people coming from all over town to enjoy his food, with lines of hopeful diners waiting outside to experience this unique restaurant.

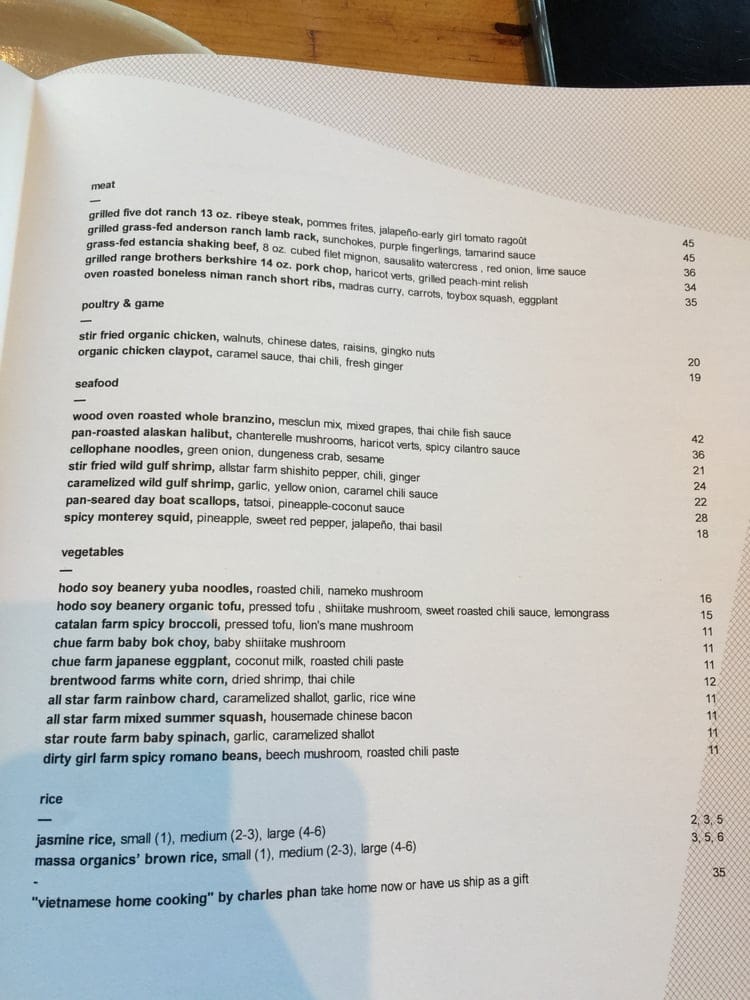

It was a different time then; the Slanted Door introduced many people to Vietnamese food (what an amazing intro to have), and I remember Phan (a self-taught chef) wanted people to try dishes beyond the bánh mì that you’d find in the Tenderloin. We became obsessed with his Dungeness crab and cellophane noodles, his daikon rice cakes, his spring rolls with Gulf shrimp. He famously wouldn’t put phở on the dinner menu—it was for lunchtime only (kind of like an Italian not offering a cappuccino after the morning).

He was dedicated to using local, sustainable, humanely raised, and the freshest quality ingredients that tasted the best—I remember it was the first Vietnamese place that was famously using Niman Ranch filet mignon for its shaking beef dish. By the time they moved and opened in the Ferry Building in 2004, the menu grew to become a veritable who’s who of the best local farmers and purveyors—from Hodo Soy tofu to Star Route spinach to special ingredients he had farmers grow for him—and organic chicken in the claypot.

His modern and ingredient-driven take on Vietnamese food wasn’t the only groundbreaking thing: I remember dining on the mezzanine at the Slanted Door on Valencia was where I had my first saison beer—the list of beers there was legendary. They also served excellent and adventurous wines selected by Mark Ellenbogen to pair magnificently with the food, like riesling and grüner veltliner, with the care of a fine-dining restaurant. (And beautiful teas, too.) I recall the staff was so cool, and smart, and provided such friendly and fun service. The place was on another level, and had such a vibe.

Bob Rosner recalls the New Year’s Eve parties at the Slanted Door were epic, with people dancing on the tables. He adds it’s why Charles was so dedicated to reopening the Slanted Door on the currently beleaguered Valencia Street—he wanted to bring some life back to the neighborhood where his career began, and give back to the community (fun fact: Phan went to Mission High School). Gayle Pirie of Foreign Cinema remembers: “It was such an awkward space. But he made Valencia Street sing. He celebrated the terroir of the Mission.”

Something I have always appreciated about Phan is what a dreamer and innovator he was—even if a concept wouldn’t work out, undaunted, he would try something else. Out the Door, Wo Hing General Store, Heaven’s Dog, the second iteration of The Moss Room, South at SFJAZZ, The Coachman, Hard Water, Chuck’s Takeaway—each place offered him the ability to celebrate something nostalgic about his past, or a passion, including Southern food, bourbon, and even, eventually, bánh mì. He wouldn’t be limited to just one cuisine or style—he enjoyed creative concepts and was always pushing, and his teams reflected that ethos, from his architect-of-record Olle Lundberg to his bartenders.

Who would have ever imagined he’d open a Slanted Door in Beaune, France? And after announcing the return of the Slanted Door at the Ferry Building, an iconic location for his restaurant, who would’ve thought he would ultimately decide to not reopen? Charles charted his own waters and made his own decisions, often unexpected ones. He was gonna do what he wanted to do, no matter what people thought. He was stubborn and passionate. A true artist.

Faith Wheeler noted that Charles didn’t have the same relationship with fear that many of us have—that he was “desensitized to it.” She wrote: “I often wondered who I would be if I was a boat person who would arrive in the country during the fall of Saigon. On a boat at age 13 when my mom tells me I’m on my own. Trying to figure it out, in a new country, with nothing.” He stared fear in the face when he was 13, and had conquered it by the time he was a young adult and making his own decisions.

Jossel adds, “During Covid, I remember we were having dinner and talking about things, and Charles said, ‘I’m not scared, I was a refugee. This is nothing.’ Man, he had balls…I’m not ready for him to be gone. He was far-reaching. He broke ground with courage and grace.” I have been seeing the word courage used in a bunch of posts about Charles, and Faith reminded me of the root of the word, cœur, the French word for “heart.”

We have our local restaurant/culinary oak trees: Judy Rodgers of Zuni, Alice Waters and Jeremiah Tower of Chez Panisse, and when we look at his life’s work and story and legacy, Charles is definitely another tree. For the past three decades, he has created such an impact, not only on our local culinary scene, but also how Vietnamese food is perceived, known, and valued on a global scale. He showed the importance of making food with the most sustainable ingredients possible, and helped destroy the longtime trope that Vietnamese food can only be cheap and casual. He has inspired countless chefs, from Asian American chefs cooking heritage-style food, to self-taught chefs, to immigrant chefs. So, a little bit louder for the folks in the back: immigrants are the people who make America great.

Chef Rob Lam of Lily texted to me: “Without Charles there is no Lily. He made our path possible. A minority-owned business with a vision of serving people his culture, brilliantly. He took Vietnamese food off the streets and into the dining room. So much of our city’s food and beverage identity is tied to this guy. I’m shocked and humbled by his legacy. We lost more than a man, we lost an ideology.”

Another big branch on this tree is all the bartending talent that has worked at Phan’s restaurants, including Thad Vogler (Slanted Door, Bar Agricole, Trou Normand), Erik Adkins (Slanted Door, Hard Water, Wingtip), Jennifer Colliau (Slanted Door, The Interval, Small Hand Foods), and Brooke Arthur (Wo Hing, Range), all groundbreaking in their own ways. Speaking with Erik Adkins, he shared a list with me of everyone else who worked for Charles, including Eric Johnson, Jon Santer, Jackie Patterson, Trevor Easter, Erik Castro (briefly), and Craig Lane. It’s such an interesting component to Phan’s legacy. He even had a nonalcoholic drink program at Wo Hing, back in 2011.

The Slanted Door didn’t serve cocktails until it moved to Brannan Street in 2002, where it was on the forefront of the craft cocktail movement. Opening bar lead Thad Vogler was given free rein to have the bar program mirror the kitchen’s Slow Food ethos and use organic, well-sourced, seasonal ingredients, with no modifiers or industrial, mass-made products. Erik Adkins (who took over when Vogler left for Guatemala to work for a nonprofit) tells me they didn’t want to invent Asian-style drinks—like the kitchen menu, they wanted to tell a story of heritage, so the bar focused on historical classic cocktails.

I enjoyed hearing Adkins tell me about the incredible family meals the staff would enjoy at the end of their shift, which would include the shaking beef, rack of lamb, and whole fish. He said they would be able to order all the food on the menu, which was unheard of: “They treated everyone like family, and we’d all eat together. They were selling food, not class distinction. It was such a fresh way of treating employees, and it ended up being a great way for us to know all the dishes so well.”

He also noted that since there were so many family members who worked at the restaurants that it was kind of a “built-in morality test”—if you were a new hire and didn’t show everyone respect, starting with the dishwasher (who was a brother-in-law’s uncle), well, you weren’t going to be a good fit.

Adkins remembers one time seeing Charles mopping at 1am after an opening party at Hard Water, so he quickly realized that he better help, too—he learned everyone had to show up, and no task was beneath anyone. Charles was so hands-on—Adkins told me the story of when they were in the Presidio prepping for a wedding reception, and Charles noticed the outdoor brick grill wasn’t level, so he took it apart, fixed it in 20 minutes, and he was on to the next thing. He was that kind of guy.

Adkins has fond memories of traveling with Charles, including many trips to New York for the James Beard Awards (he won Best Chef: Pacific in 2004). Slanted Door was nominated so many times—Charles even flew his staff to New York once, and, of course, Slanted Door didn’t win that year, but they finally cinched Outstanding Restaurant in 2014. When they had a giant celebration party at The Coachman, Charles passed his James Beard medal around so people could wear it and take pictures with it all night. It ends up the medal went missing until the next morning, when a line cook cruised in to work, proudly wearing it around his neck.

Adkins was thrilled that Charles was with him when they went to Tales of the Cocktail in New Orleans together in 2012, and Slanted Door ended up winning for Best Restaurant Bar. They went to Louisville for bourbon barrel pick trips, and London for R&D for The Coachman. Adkins remembers one night in London when they went for a pre-dinner at a place Charles was curious about, then a feast at one of Heston Blumenthal’s restaurants, and ended up for a third meal in Chinatown at 3am, eating tendon and tripe and whatever else Charles spotted. He said you had to buckle up and down for nights out with Charles, and be prepared to eat everything and have a late night.

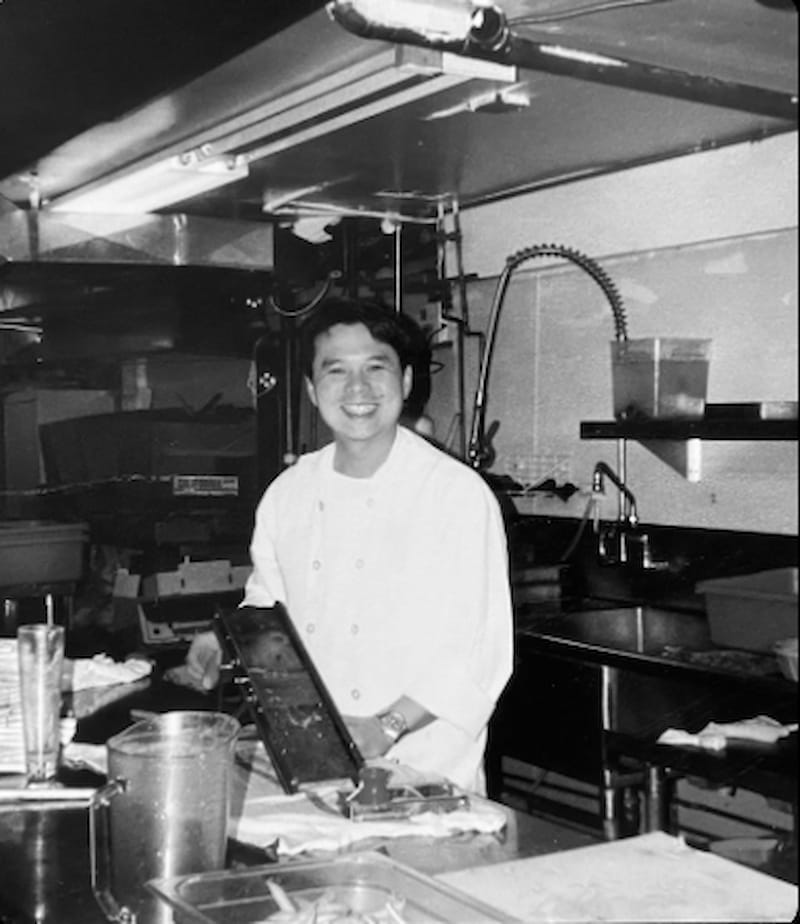

While we were talking, I shared my observation that no matter how high-profile Charles was, he kept an exceedingly low profile. Unless you worked with him or were a close friend or joined him for a few late nights, you wouldn’t know that much about him. Adkins agreed, noting that he worked for Charles for five or six years until he knew about Charles’s early years in the garment industry. He was always focusing the conversation on others, not himself.

Phan was deeply respected for being kind-hearted, instead of the number of TV shows (including Iron Chef) or magazine covers he was on (although we cheered him on for that, too). His good nature and approachability helped make him a mentor to many people, or just exceedingly helpful to others…he had the true spirit of how you build and nurture community.

Shelley Lindgren of A16 posted this beautiful tribute: “Always a friend to us all—sharing his knowledge and his most joyful laugh. Charles was a one of a kind, beautiful human, always something funny or wise to share, a visionary for his family and had the courage to build his dream.” It’s true—he loved to laugh, and always had that impish smile, and twinkle in his eyes (along with some red cheeks if it was getting late and there was some bourbon on the bar).

I caught up with Paul Einbund of The Morris, who Phan hired in 2010 as a consultant for six months—Einbund didn’t want the contract to end, but he said he was grateful the relationship never ended. He recounted how Phan would later come into The Morris all the time for meetings and meals, and would compliment the food and drinks. Einbund shared the story of a fish sauce martini he was developing (for nine months!) as an alternative to a dirty martini made with olive brine, and he deeply loved Charles’s nước mắm (fish sauce). Guess who brought Einbund a gallon of it to use? That’s how he was. This is how to show up.

I feel so incredibly fortunate to have lived during and later reported on such a golden period for restaurants in San Francisco. The late ’90s and early aughts were a special time to be a chef, or a bartender, or a server, and the restaurant and bar community was tight. It was an era of innovation and community and energy.

As those chefs are aging out, or leaving the industry, or closing their restaurants, or, in this case, tragically dying, I worry a bit for the next generation of the chef community. So many people are focused on survival that they aren’t taking care of each other or the larger community. Wheeler noted to me that the scarcity vibe seems to be more present these days, but she reminds us: “That it always comes back, it’s psychic income. You always feel better after the giving.”

I hope some chefs (heck, anyone) will be inspired by these stories of how Charles showed up, whether it was at a restaurant’s bar or charity gala or mopping a floor at the end of the night. How he gave, hard. How he cared. His level of altruism is needed now more than ever to get us through these dark times, but he has left us.

Fortunately, we have his legacy to learn from, his deep and shining example of what it means to give, and to love. So, in his honor, give back—and then give a little harder. Show up for your fellow chefs. Check in. Go out and eat at a restaurant that would be honored to see you. Offer up your basement of supplies. Be a mentor. Become a master of magnanimity—it’s a much better legacy than just being remembered for a famous dish. 💫

the sponsor

Celebrate the Essence of Sardinia at a Mirto Day Dinner at Montesacro Marina on January 29th

The annual Mirto Day is here! Immerse yourself in the beauty and history of Sardinian mirto, a classic liqueur and digestivo made from an infusion of myrtle berries in alcohol. On Wednesday January 29th, Montesacro Marina (3317 Steiner St.) is hosting a dinner dedicated to this distinctive liqueur from Bresca Dorada, which produces mirto in the southern part of the island and harvests the berries by hand.

The dinner will start with an aperitivo cocktail made with Mirto Verde, while the kitchen has crafted a menu inspired by Sardinian flavors, from traditional malloreddus (thin ribbed, shell-shaped pasta made with semolina and water, saffron kissed and cooked with fennel seeds, sausage ragù, and pecorino) to the indulgent raviolini filled with ricotta and served with warm Sardinian honey.

$100 per person; includes a three-course tasting menu, expertly paired wines, a welcome aperitivo cocktail, and a digestivo to complete the experience. Guests can book directly through this link. 4pm–9pm. Seating is limited—don’t miss this journey into Sardinian tradition!